West Bandung Landslide: ITB Expert Explains Mudflow Mechanism and Potential Secondary Hazards

By Merryta Kusumawati - Teknik Geodesi dan Geomatika, 2025

Editor M. Naufal Hafizh, S.S.

BANDUNG, itb.ac.id - The landslide that occurred in West Bandung Regency (KBB) on January 24, 2026, should not be understood solely as a consequence of land-use change. Landslide geology expert from Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB), Dr. Eng. Imam A. Sadisun, emphasized that the event resulted from a complex interaction between natural geological processes and human activities, leading to a mudflow mechanism triggered by landslides in the upstream section of the slope–river system.

The mudflow path crossing Kampung Pasir Kuning to Pasir Kuda, Pasirlangu Village, Cisarua District, West Bandung Regency (Source: ITB PPMB and DPMK Team).

According to Dr. Imam, the West Bandung area is underlain by old volcanic deposits, which naturally develop thick weathered soil layers. The boundary between these weathered materials and the underlying, relatively impermeable bedrock often forms a slip surface. Prolonged rainfall further weakens this condition by allowing water to infiltrate and saturate soil pores.

“When soil pores become fully saturated, the shear strength of slope-forming materials decreases drastically. Under such conditions, slopes often fail to support their own weight,” Dr. Imam explained.

He added that landslide initiation is controlled not only by rainfall duration but also by rainfall intensity. In geoscience, the relationship between rainfall duration and intensity shows that moderate rainfall lasting for a long period can be as hazardous as short-duration, high-intensity rainfall.

Not Merely a Local Landslide, but Sediment Transported from Upstream

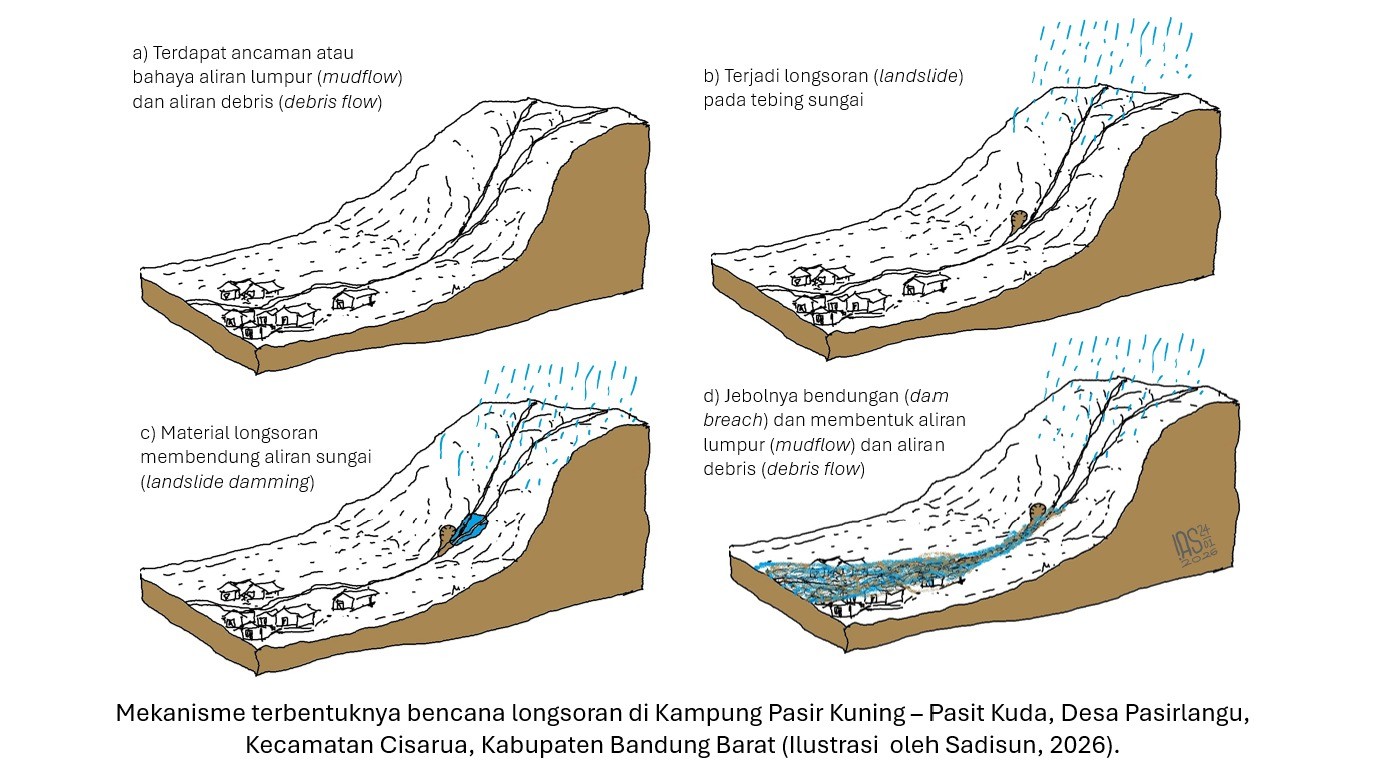

One of the key findings from this event is the indication of a landslide occurring in the upstream section of a river system on the southern slopes of Mount Burangrang, which blocked the river channel and formed a natural dam (landslide dam). As the channel was obstructed, water flow was temporarily impounded upstream, accompanied by the accumulation of sediments such as mud, sand, and large boulders.

When the natural dam could no longer withstand the increasing water pressure, it collapsed and triggered a mudflow moving downstream along the existing river channel. This flow was not merely water, but a dense mixture of mud carrying boulders and woody debris, moving at high velocity and causing severe destruction.

“Houses were not destroyed by landslides on the slopes where they were built, but were impacted by landslide material transported from upstream through the river channel,” Dr. Imam stated.

Such flows generally possess far greater destructive power than ordinary floods due to their extremely high sediment load. Therefore, this phenomenon is more accurately classified as mudflow, or in some cases, debris flow. This explains the severe damage observed along the flow path and riverbanks, even in areas located far from the original landslide source zones.

Dr. Imam also warned of potential secondary hazards, as indications of remaining blockages were still found in the upstream river sections. If intense rainfall occurs again, water accumulation behind these obstructions may collapse once more, triggering additional hazardous mudflows downstream.

High Vigilance Required for Communities Living Along Riverbanks

Although most affected areas are regionally classified as having low to moderate landslide susceptibility, Dr. Imam emphasized that many settlements are located within river buffer zones, which are highly vulnerable to mudflows and debris flows originating from steep upstream slopes.

“Hazards do not always originate from the slope on which a house is located, but may come from connected flow systems linked to steep terrain upstream,” he said.

He also highlighted the critical role of vegetation in maintaining slope stability. Vegetation contributes mechanically through root systems that enhance soil cohesion and hydrologically by reducing the rate of soil saturation during rainfall.

Science-Based Mitigation Strategies

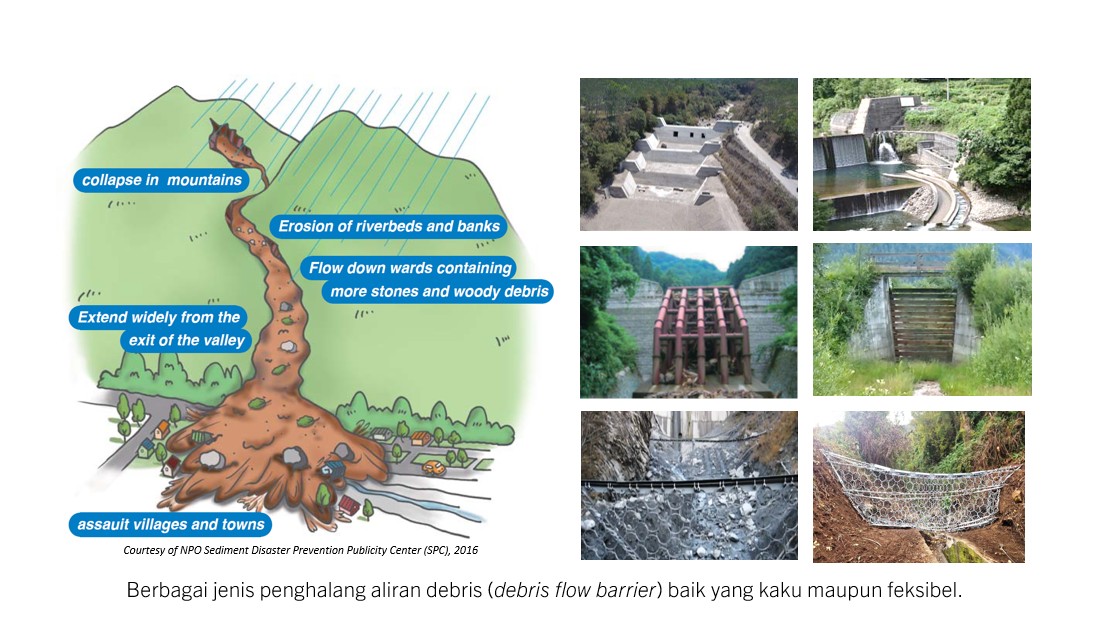

To address mudflow and debris flow hazards, Dr. Imam outlined three primary mitigation approaches. First, slope stabilization in upstream areas, particularly on slopes that may act as sources of landslide material and block river channels. Second, monitoring of flow paths using technologies such as geophones, vibration sensors, and surveillance cameras to detect early material movement. Third, downstream protection measures, including debris flow barriers, deflection walls, debris fences, and debris flow catch basins.

“The most destructive element is not the water itself, but the sediment carried by the flow. Therefore, mitigation systems must focus on controlling the sediment,” he emphasized.

Natural Warning Signs to Watch For

As part of non-structural mitigation, Dr. Imam stressed the importance of public awareness of natural warning signs. One commonly overlooked indicator is the sudden decrease or disappearance of river flow during ongoing heavy rainfall, which may signal upstream blockage or impoundment.

“If a river that normally flows suddenly recedes during heavy rain, people must remain alert and immediately move away from the river channel,” he warned.

Through this event, Dr. Imam hopes that public understanding of landslide hazards will extend beyond the collapse of slopes alone, to include the risks posed by sediment-laden flows and mudflows originating upstream, which can strike downstream communities without obvious visual warning signs.

Reporter: Merryta Kusumawati (Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering, 2025)

.jpg)

.jpg)